Aaron Sing Fox and Daniel de la Nuez of Forthave Spirits

Issue 33: On their creative process, shifting consumer tastes, and their favorite way to drink Aperitivi.

Why hello there! Welcome to on hand! If you’ve landed here and somehow aren’t subscribed, I got you:

Forthave Spirits is a botanical spirits distillery founded by friends Aaron Sing Fox and Daniel de la Nuez. The pair looks to history for inspiration and crafts spirits using botanicals from their library of over 200 different types of herbs, roots and barks, leaves and flowers, and fruits and seeds. It’s a small operation but they’ve gained a cult following and their spirits are showing up across the menus of high-end restaurants.

I sat down with Aaron and Daniel in their production-facility-slash-science-lab to chat about their creative process, shifting consumer tastes, and their favorite way to drink Aperitivi.

Brianna Plaza: What's your background?

Aaron Sing Fox: I got into the world of wine and spirits when I was in college. I studied art, then moved to Paris and got a job in a wine bar; I really fell in love with it. I decided I wanted to make my living in that and keep art as my hobby.

So, that was how I got into it and I did lots of stuff in the wine and spirits world. I was beverage director at different restaurants in 2012 and I started fooling around with making these botanical spirits. Which is a different path and new passion for me, whereas most of it had been wine. Wine is this beautifully singular idea of you don't have any ingredients except for the grape — it's fermentation and how many flavors and directions you get from that. With spirits, you are mixing ingredients and it's a different way to investigate history.

I started really going down that rabbit hole. And that's when Daniel and I became friends — he’s the other half of Forthave spirits — he was a journalist and one of the founding stars in this.

And Daniel tasted some of these and we were having dinner, and he was like, "Oh my God, how was this made? It's so interesting." And I was like, "I really don't know." I had limited resources and very few books to make stuff like this. If you look at spirits, there's a lot of mystery to these. There's a lot of smoke and mirrors in spirits in general, but certainly in our category, there are a lot of secret recipes.

There were a couple of books that we got, but most of those are very old style books. They have information on how spirits were made in the 1800s or how they were made in the 50s. So, we started playing from there. Daniel was like, "I've got some more room in my kitchen and dining room." So, we went to the home brew store and bought everything that we could get.

We got funnels and jars and just started doing the first basic infusions in different types of alcohol. We were buying brandies and neutrals and just infusing and mixing. Infusing water or cooking them or what not and making the first blends. And filled up all the space we had. And that's when it just started organically evolving. At that time I had a painting studio on Governors Island, when they were doing those first studio spaces there for LMCC. That residency was coming to an end so I needed to move all my paintings and my work.

Daniel was writing and he had a little office. We got a space in this building and just moved all of those things here. We moved the painting studio, the writing/producing office, and then quickly just fully filled it up with all our experiments. Which is when we started expanding to what we wanted to make, that was the experience.

Brianna Plaza: Is a botanical spirit something that you add botanicals to - is that how it's categorized?

Aaron Sing Fox: That’s how we categorize it. This all started from a love of Amaro, which expanded to Aperitivo. And then we've got lots of stuff we really want to do, like an Italian-style Amaro in Brooklyn, and we wanted to do the larger category of botanical spirits. So that includes gin, the most widely known botanical spirit out there.

So much of the liquor industry is sold by big brands. I think most of the industry wants to be a brand as opposed to connected to a process or what it's made from. Gin, for example. It's often considered closer to vodka than to absinthe, but I would consider it closer to absinthe than to vodka. We’re making a distinction between those straight spirits, which are those that have some sort of natural potential for fermentation.

So, if it's a brandy, which has free sugars and waters, you can ferment any fruit that has those. Or stuff in the whiskey realm where you have grain and you have to do a conversion of starch to sugars, and then do fermentations and distillations from there. You’re expressing a version of an alcoholic fermentation through distillation.

Brianna Plaza: As you're building a brand and figuring out what you like, how do you account for the fact that things take time to taste good or bad?

Aaron Sing Fox: Time is a huge piece of it. When we started we had several years of doing it for ourselves, and that informed a lot. And then thought, "What would it take to sell these?" So, the distillery we looked into, we DIY-ed everything. We had to navigate through licensing and that takes time.

So, that gave us another two years to really refine our processes and experiment. How long does a batch of Marseille - once we know the recipe - how long does it take? It varies because there are many different factors. Humidity, barometric pressure, and so on. So, over the years we've been able to hone it down by taste. We'll taste a batch once it's finally finished — it’s the last step in a multi-step process over 15 months — then as long as it has what we call the soul of Marseille, then .. it's time.

We think of it like a flow through here, so there's botanicals and spirits over here, there are infusions in different spots, it flows through these different steps until it’s at a spot where we can bottle it. And then that opens room for new stuff to come in. So once that's moving, you have areas where you can develop something new and explore your creativity, but a lot of it you're just putting new stuff in as older stuff moves out.

We have some stuff that’s aging three months, but gin is quicker to make and you can make a batch in a couple of weeks. But some of the stuff, like the Nocino, takes 18 months, and then some of the reserve or single batch stuff can take more like three years. So to develop a new product, so far, three years is about as quick as we've developed something new. I always think we can develop one a little quicker than three years, but so far we've not beat that.

Daniel de la Nuez: We hold ourselves to high standards.

Brianna Plaza: How do you decide what botanicals you want to use? Tell me about your creative process.

Daniel de la Nuez: When we first started talking about what our bottles would look like, we thought we wanted to have an architecture to our labels. So, we have a color line, blue is our gin, red is our Aperitivo. Red is essentially where we do our take on a classic botanical spirit. For our Amaros it didn't make sense to do it in the color line, because they vary so greatly throughout different continents, not just Italy.

If you want to make wine, there are a ton of books. Whiskey, there are tons of books. But making Amari in 2013, there were no resources. So, we look at the history of botanical spirits and we found that they all have this history of herbal medicine. So, we decided that having learned how to extract aromas and flavors through herbal medicine, what would be interesting would be to make our first Amaro as the first of our historical line. Marseille is based on a recipe that's attributed to our namesake, Richard Forthave. He’s attributed to coming up with a plague remedy.

So, that lore fits that one. When we come out with our next one I think that will come more into focus, the historical line. So when we do newer products, what we will do, we'll find an ingredient. Let's say something that's not traditional. Let's say for instance Chaga mushrooms. Chaga is a big mycelium that grows on birch trees all around the North East. A chef had given us some that he'd foraged on his property and brought it down.

So, we're doing little tinctures of it and Aaron had the thought, this tastes almost like an aged rum. Well, let's work with this some time. But we're not going to be able to fold it into Marseilles, that recipe's set. But there’s no Chaga category, no-one's really used it before, so that's where our single batch line comes in. And the single batch is where Aaron and I get to have fun. So, we got a cool ingredient, let's play with it, let's do different extractions, let's see what we can do with it. Macerate it in water, in ethanol, distill it, and so on. So, the single batch line allows us to find new ingredients and play with them.

If, say, we get an ingredient that is used in a broader category, for instance Genepi flowers. And Genepi flowers, if you aren't familiar with them, they're fascinating. They're these beautiful flowers that grow in the Alps, the French and Italian Alps, above 2,000 meters. And it's a traditional thing you'll find in the Alps as an après ski. So, what we'll do is we'll try to find as many Genepi spirits as we can domestically and then travel and bring a bunch back and then really get to know what the category is. Contemporary ones, vintage ones as well.

So then we say, "Okay, what would we do with it?" The traditional style of Genepi is like Chartreuse; a herbal liqueur - high alcohol and higher sugar as well. But we found the flowers to be so delicate that we said, "Let's do it in a different style." So, we did it as an aromatized wine. So, we had a natural winemaker friend up in the Finger Lakes make us a cuvée for the first one we put out and did it in that style. So, it's really about when we do find different ingredients and experimenting. Is it part of a category? If it's not, where is it going to land and how are we going to experiment with it?

Brianna Plaza: How do you source other new botanicals?

Aaron Sing Fox: It depends on what we're looking for. We make a coffee liqueur and it came about because we're friends with a coffee roaster that's also in this building. We had this idea to try and make a coffee liqueur at the level of the top coffee programs. When we started developing this there wasn't so much of an espresso martini craze. We found other coffee liqueurs were really stuck in this certain era of coffee. But coffee roasting cultivation has gotten so high, that the intentionality was to have a coffee liqueur to reflect that.

Daniel de la Nuez: We worked with Caesar and his company to decide on a bean. We wanted to do something on that level, so it was going to be a single-origin bean.

Aaron Sing Fox: There was one farmer who's known as the vigneron of coffee and he experiments with different fermentations. And there was this one bean that we fell in love with. And I know the grower he sends it to and Caesar says, "This is a roast from Japan" and that's really it.

Daniel de la Nuez: It’s a very specialized coffee. So, that would be a story of how that one came about. Then the black walnuts that we harvest for the Nocino, those show up throughout the summer. I have some states where I'll keep an eye on trees that I think will ripen this year and then we'll...

Aaron Sing Fox: Drive, we all go up and hit the spots of origin.

Daniel de la Nuez: Yeah. I've got a bunch of those long pickers, they're 40 feet long, get up in the trees and we just fill back of the truck with walnuts and process them. And then for many other things there are spice vendors we work with to get these beautiful coriander from Egypt or Moroccan rose petals. Those ones we're sourcing the highest quality organic that we can find.

Brianna Plaza: How do your creative backgrounds inform how you work and where you are going to move this company next?

Daniel de la Nuez: Aaron's got this synesthesia with flavors and colors, as a painter, and as this drawing professional. So, that's really fascinating.

Aaron Sing Fox: I think with both of us, what we're trying to do is tell a story of botanical medicine. Sorry, not botanical medicine, we're trying to sell botanical spirits.

Daniel de la Nuez: We can’t say it's good for you.

Aaron Sing Fox: Yeah, we're definitely not doing botanical medicines.

But we're trying to tell the story of these botanical spirits. And so, each successive release is about expanding and investigating what we want to say. And what we're curious about personally.

Daniel de la Nuez: I mean it started as a creative endeavor between two friends. And Aaron's painting comes in through the labels. We’re two creatives coming up with this concept and telling this story. When we first started there were very few, if any, domestic Amari and Aperitivi producers at all. It was really important for us to explain to people where they come from, how they're developed. As a producer it's great.

Aaron Sing Fox: One of the things that we're doing now, well actually we have been working for three, maybe even four years actually, is this mixed fruit liqueur, you could say. We wanted to look at all of the abundance that New York produce has to offer and make an expression of that abundance in a fruit liqueur.

Daniel de la Nuez: When we ask most people what fruit and produce comes from New York, they'll say apples, maybe pears. But there’s so much more: peaches, tomatoes, cherries, ground cherries.

Aaron Sing Fox: We did buy thousands of dollars worth of ground cherries. It was a huge amount but the yield was actually very small.

Daniel de la Nuez: Yea we were just juicing them for days and days.

Aaron Sing Fox: It's been a fun thing to investigate. It's been aging and blending, and because it's based on New York’s seasons we only have this little bit of time to do it. So, that would be one version of what a product would eventually be and the why.

Brianna Plaza: How have you seen consumer tastes change since you started this business - especially over the last two years?

Aaron Sing Fox: Yeah, it's interesting because when we started we were in — I guess we still are in this arc of — a certain point of farm-to-table restaurants becoming most of the top best restaurants around. And then wine programs start to reflect that and then the beer programs start to reflect that. And quite a bit later the spirits programs start to reflect that. And I think we're still somewhat in that shift.

Daniel de la Nuez: We were speaking with a natural wine importer recently and they were telling us it's still difficult to make spirits that are sustainably made with organic ingredients with all these new distilleries that are coming out. That's something that we really want to inspire and create this category. And I think like Aaron said, it's growing, but hasn't been as quick as, say, restaurants or wine for instance.

Brianna Plaza: Why do you think there's been a lag in this category?

Aaron Sing Fox: Well, there's a number of different things. One is that the big spirit brands just control everything. So, that's a piece of it.

Daniel de la Nuez: The smaller ones are just really expensive. The things that we use cost a lot of money.

Aaron Sing Fox: I think with consumer taste, people have become much more adventurous and interested in what goes into the bottle and what they're consuming in all sorts of things in their life.

Daniel de la Nuez: In a broader scope, I think having grown up both in the US and in Europe, bitterness is not something that's in the American tradition. That's something that we've seen move very quickly in the last two years. The embracing of the Aperitivo and the Digestivo after dinner. We've been really happy to see that American culture's really embraced it.

Aaron Sing Fox: Yeah, that has definitely changed a lot. And people wanting to buy from small producers, that has shifted a lot.

And I mean there's also the whole cocktail renaissance. Any of the good restaurant programs and bar programs have a real specific dedicated creative team behind that. That's totally different. I remember when I was first going out to bars in New York and it was really just...

Daniel de la Nuez: Shots, beers, Ketel and cran.

Aaron Sing Fox: Yeah, there was a lot of that.

Brianna Plaza: How should I be drinking Aperitivi and Amari at home?

Aaron Sing Fox: I mean I think the Aperitivo piece to it is to make something very light and appealing to wet the appetite.

Daniel de la Nuez: It's physiological, right? So you’d drink an Aperitivo to open the appetite. Bitterness plays a role both at the beginning and at the end of your meal. So, when we have some before a meal, it's going to activate your digestive enzymes. If you think of a fresh piece of orange, your mouth's going to start watering, it activates the salivary glands and starts making you hungry. Likewise after a meal, you just had this large Italian meal, like we did last night, you're going to feel really full and having an Amaro afterwards is going to do the same and start your digestive system. It's going to start making you feel better.

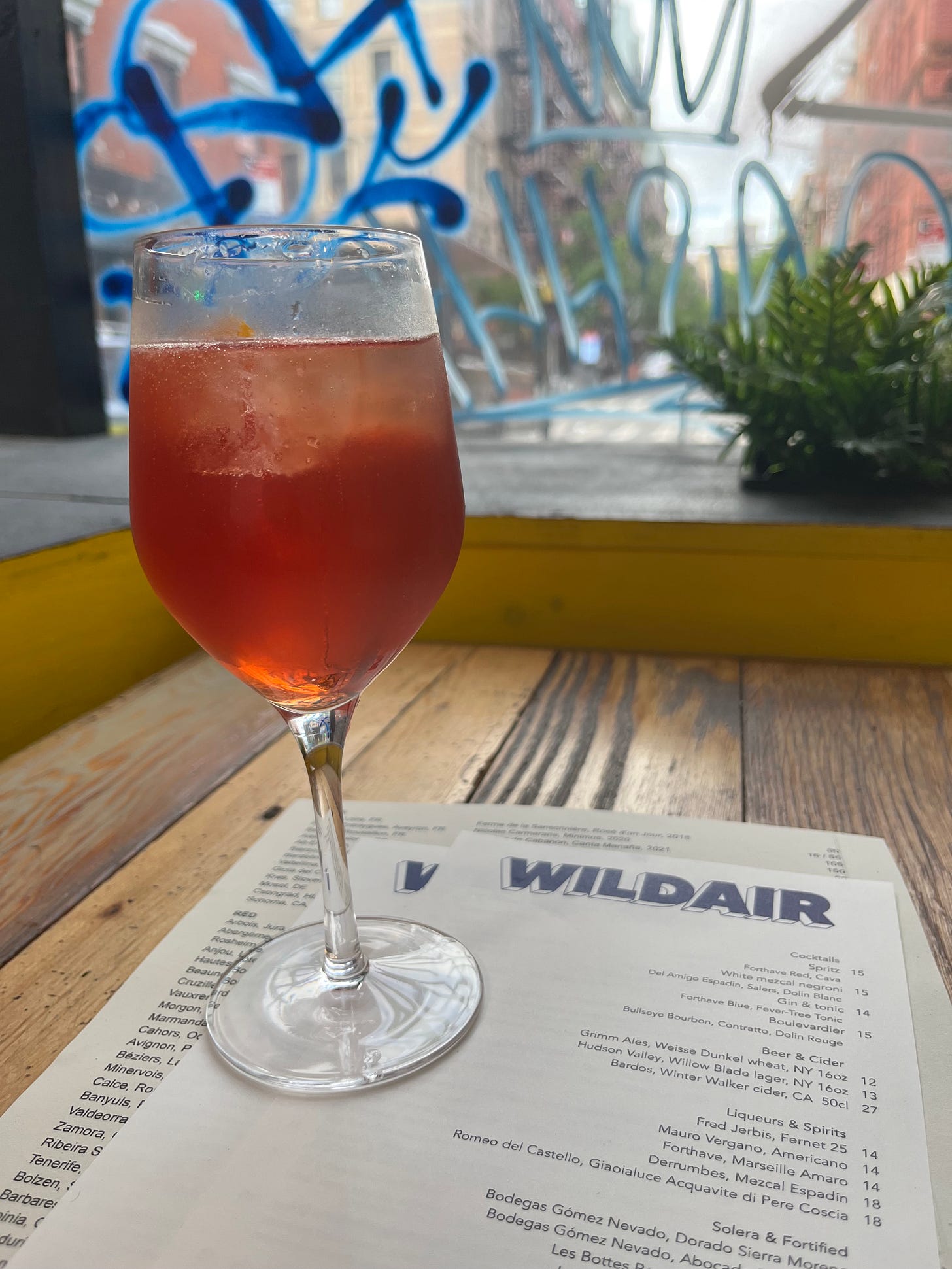

I think the best entry is to do it very simply - when you sit down at home before your meal, or you go out to a restaurant, have an Aperitivo with club soda and ice, or with a pet-nat as a spritz.

Aaron Sing Fox: You can mix soda water and pet-nat with Aperitivo if you want it a bit lighter.

Daniel de la Nuez: And then for the Amari, have it neat after dinner. Maybe if it's summer throw an ice cube in it. It's very simple, it's a great way to start. Without having all these big cocktail recipes.

Other things ~

When I moved to New Jersey for college, I learned that the Northeast - but especially North Jersey - has a very unique vocabulary of Italian-ish words. Atlas Obscura looks into How Capicola Became Gabagool and explains New Jersey’s unique Italian accent.